Bikepacking & Packrafting the Lost Coast of Alaska: Part 2

October 17, 2016

Words & Photos by Don Carpenter

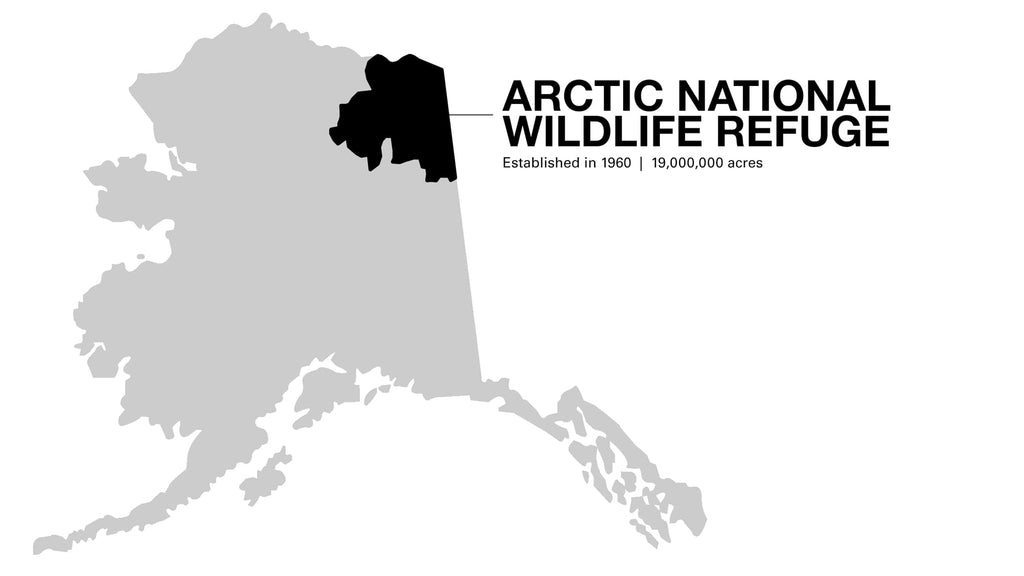

[Note from Don] When I wrote this story, I had no idea that the debate over drilling within the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge would surface again so soon. This debate has gone on for decades, and drilling is again on the table. The US Senate has just passed a tax bill that includes an amendment that would allow drilling on the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge. The House of Representatives and the Senate need to reconcile their bills and then it will go to the President. If you are opposed to oil development in this place, now is the time to speak up. If you are so inclined, please let your representatives know you are against drilling in this incredible place.

Alaska’s Arctic Wildlife Refuge is awe inspiring- it is big, wild, remote country. Mountains are stacked upon mountains, interspersed with free flowing rivers. The Refuge stretches from the south side of the Brooks Range, over the glaciated high peaks of the range, and across the coastal plain to the Arctic Ocean. I often marveled at the remoteness, as I realized how far we were from the nearest village or road.

We had been following fresh wolf tracks up an unnamed drainage since leaving the main river canyon. We knew they must be close by, but hadn’t seen any yet. Greg was the first to spot it on the hillside above us. We watched as the gray and black wolf moved up the slope and then lay down. What followed was an intimate interaction with a family of wolves in a wild and remote landscape. Barks grew into howls and a series of calls and responses rang across the valley. Soon, young pups appeared on the other side of the canyon. We listened to a symphony of howls for over an hour and watched as the family regrouped and slowly made their way into another side drainage.

Logistics can be challenging for an Arctic trip. To maximize our time in the Refuge, our group chose to fly in and out with Kirk from Yukon Air. This added some cost, but offered us the most time in the hills. We flew into the south side of the Brooks Range, hiked over the continental divide, navigated 3 rivers out of the mountains, crossed the coastal plain and ended at the Arctic Ocean. Traveling a total of 160 miles over 14 days.

However, we were not going to the Arctic Refuge to travel 20 hours a day. We wanted time to take everything in- to savor morning coffee, fish, look for animals, and enjoy the magic of the Refuge. Thus, we travelled light, but we weren’t focused on a few extra ounces. We had plenty of food, including makings for pizza and pancakes, and even had whiskey left to toast the friends we’ve lost when we arrived at the Arctic Ocean.

I had high expectations for the trip. And the Refuge exceeded them all, easily. Our pace allowed us to take in the wonder of the Arctic. We enjoyed surreal moments in camp basking in the midnight sun, watching birds, and glassing for animals. Our pace also lead to several wonderful animal interactions… watching and listening to the pack of wolves and observing a grizzly for over an hour from a hillside above camp.

Traveling by foot and packraft through the Brooks Range was stunning, but the coastal plain was truly unique. This plain can seem barren from afar, but I found it beautiful, diverse, and vast. We saw a large variety of birds and waterfowl— eagles, jaegers, harriers, harlequin and merganser ducks, tundra swans, geese, gulls, arctic terns, plovers, sandpipers, and many other songbirds. Many of these birds were nesting on the coastal plain.

The fragile tundra of the coastal plain was teeming with wildflowers and we saw signs of bear, wolverine, and wolf. We also experienced fata morgana— an Arctic phenomenon that produces mirages and made it appear that the pack ice on the Arctic Ocean was inland ice cliffs that could be impassable.

We knew there was a good chance of encountering large numbers of caribou on the coastal plain. The Porcupine herd, numbering approximately 180,000, gathers on the plain in June and July to calve and feed.

On our flight in, we learned from Kirk that the herd had amassed on the coastal plain, but about 30 miles west of our intended route. They might move east, directly into us, or head south into the mountains, and we would never see them. In the end, we saw very few caribou. Ironically, this lack of caribou sightings was perhaps the most incredible wildlife experience for me.

On our pick up, Kirk asked, “Have you seen any caribou, I’ve been flying, but seem to have lost them.” Last he had seen, the herd had split into two groups of 90,000, and then vanished. At 180,000 strong and with 720,000 legs, they could be anywhere. On our flight out, we finally spotted a few groups of 10,000 or so, up a small tributary of the Hula Hula. I am glad we still have country big, wild, and remote enough for 180,000 caribou to give us the slip!

A week before flying to the Sheenjek, on a trip to Colorado, my friend Dirk took me to meet Bob Krear. Bob is a 10th Mountain Division veteran, having fought in Italy during World War II. He was also a member of the 1956 Sheenjek expedition 1956 Sheenjek expedition, led by Olaus and Mardy Murie. The findings from that research expedition played a large part in the formation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

During our visit with Bob, we heard stories of fighting in the mountains of Italy during WWII, tales of the Sheenjek expedition, and from his work with the National Park Service. As we chatted on that Sunday afternoon, I flipped through a book Bob had written about his time in the 10th Mountain Division and what he had done since WWII. Bob had written that his role in the 1956 Sheenjek trip, and the part it played in the creation of the Refuge, was one of his proudest achievements. I thought of my visit with Bob often as I traveled through the vast Arctic landscape.

The work of Bob Krear, the Muries, and others from their generation, laid the foundation for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and a legacy of wilderness for future generations. As I look forward, I think this quote from Mardy Murie is as powerful today as it was in 1977.

“BEAUTY IS A RESOURCE IN AND OF ITSELF. ALASKA MUST BE ALLOWED TO BE ALASKA, THAT IS HER GREATEST ECONOMY. I HOPE THAT THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IS NOT SO RICH THAT SHE CAN AFFORD TO LET THESE WILDERNESSES PASS BY- OR SO POOR THAT SHE CANNOT AFFORD TO KEEP THEM.” – Mardy Murie // Alaska Lands Bill testimony June 5, 1977 in Denver, Colorado.

Don Carpenter is a guide, outdoor educator, and co-owner of the American Avalanche Institute. He has been guiding and teaching in the mountains since 1998 and an owner and instructor at the AAI since 2009. His winters are busy with logistics and avalanche courses at AAI and ski guiding. Spring, summer, and fall find him guiding, running rivers, packrafting, and chasing elk. Don, and his wife Sarah, live in a straw-bale home they built on the western slope of the Tetons.

Don has also shared his LNT principles in a previous post from his 2015 trip to the Refuge: Leave No Trace Principles in Alaska’s Arctic Wildlife Refuge

YOUR CART IS EMPTY

Let’s find you the right gear for

your next adventure.